By Tim Burrell-Saward

It’s Gen Con 2018. The third day I think, or maybe the fourth. Time goes a bit wonky at cons. I’m there with my old studio Sensible Object. (You might have come across Beasts of Balance, a mix of Jenga and Pokemon that you play with a connected app.) There aren’t all that many people currently making games with physical, digital, and electronic bits, so word gets around that you’re the people to talk to if you want to make the really tricksy stuff. That’s how I end up meeting Mr. Daviau.

Rob tells me about a game called Dark Tower that I’ve never heard of before — it didn’t really make the jump across the Atlantic to the UK — about how he wants to remake it, and whether I’m interested. Yes, I tell him, I do believe I am.

Fast forward to Pax Unplugged later that year. Rob and I have bounced a few ideas around over email so I jump on a plane to go meet the team, to figure out if we can work together. I meet Rob, Justin, and Isaac Childres in the lobby of a hotel, and we talk whilst we play a very early paper prototype. I don’t recall much from that early game, but I remember coming away with two thoughts:

- One: based on what I saw this game is going to be a legit classic.

- Two: I’m not quite sure how I’m going to pull it off, but I’m making this damn tower.

Jan, 2019. My time at Sensible Object is wrapping up, and I’m very much looking forward to a nice bit of R&R after four years of hardcore startup nonsense. No, wait, that’s not right. What I mean is that I’m looking forward to going straight into another crazy hard project, only this time with the added bonus of having to juggle multiple time zones. But even the hardest of tasks are achievable provided you break them down into chewable chunks, so that’s what I did.

The first chunk was working out why people remember this game so fondly. After a bit of eBay scouring, I found a copy of the original — don’t ask how much it cost — and promptly tore down the tower. Fear not, friends, the patient made a full recovery. Now, if there’s interest I’ll throw together a teardown vid, as I’m super impressed with what I found inside. But the long and short of it is this: a central rotating column, some lights behind printed acetate graphics (stunning artwork btw), a speaker (8bit SFX, not very easy on the ear), a seven-segment LED display, and a membrane keypad, all housed within a grey plastic shell. Honestly, I was pretty astounded at the sophistication contained within this 38-year-old toy, so much so that I’m genuinely thinking of going on a side quest to find out more about its development.

Once I had an understanding of what the original tower did I could begin the design process proper. The first step in this case was to bring the team up to speed on all the different options for functionality that we might want to consider. Ever since prototyping platforms like Arduino and Raspberry Pi took off, there’s been a steadily growing smorgasbord of readily available sensors and actuators to play with. From photocells that measure light to anemometers that measure wind speed. From RFID tags that you find in contactless payment cards to lasers that go pew. There’s a lot of scope for exploration.

Alongside this I started to work with the team on the new game design, and specifically on how the tower could integrate into it. I’m sure you’ve played games before that have a gimmick that looks exciting on first glance, only to find that there’s not a lot going on beneath the surface. It would be so easy for the tower to feel bolted on, an expensive MacGuffin. So it’s vital that the tower and gameplay are designed in tandem, building off the strengths of each other. From day one, we wanted the tower to feel alive, a sentient malevolent force gazing out across the land, aware of the player’s actions and able to fight back in nefarious ways. We wanted people to hate it, to fear it, and to want to destroy it.

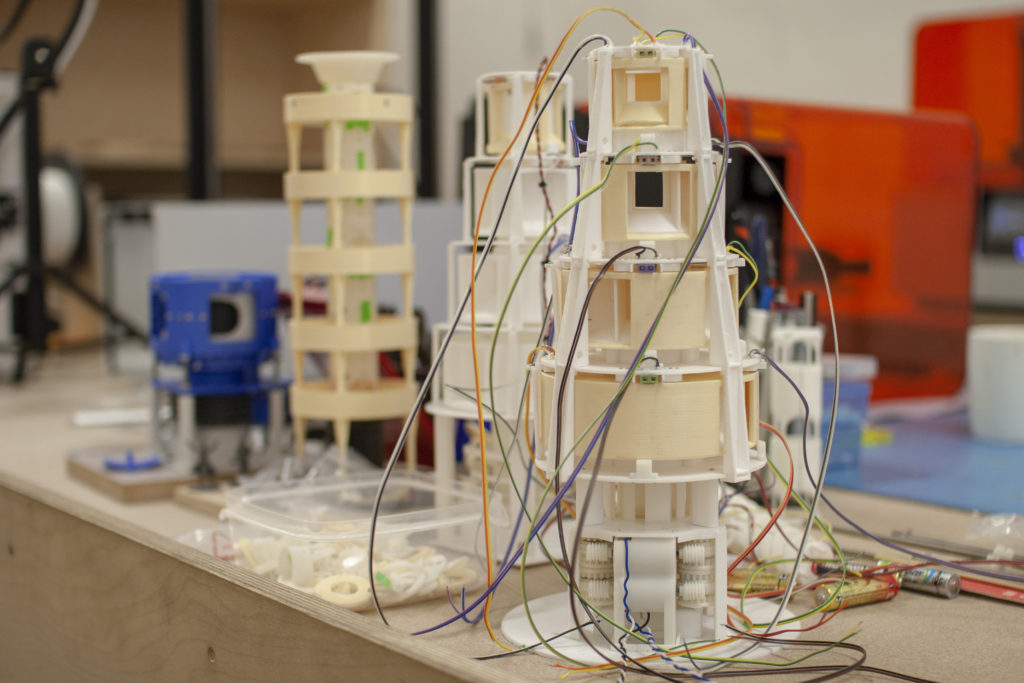

So, after a lot of back and forth between the team, we had a plan for what would end up being the first of eight major iterations for the tower. It would consist of several stacked layers, each of which would rotate independently. The core of the tower would be hollow, into which cubes — ultimately, skulls — would be dropped by the players, like a dice tower. Each layer would have apertures to allow the cubes to fall out onto the gameboard. It would have sound and light. And it would have one more thing, something that I knew from my experience with Sensible Object would prove divisive: an app.

You’ll find out more about the app as the campaign approaches, but all I ask for now is that you trust me when I say that its been designed from the ground up to be entirely integral to the experience. Like I said: no gimmicks here, guv.

So this brings the story of the tower up to around February, 2019. I knew what our tower needed to do and I knew what had come before it. So, now all I had to do was figure out how to make it….

This is the second in a series of design diaries on Return to Dark Tower, leading up to our Kickstarter campaign, launching January 14th. The first diary can be found here. If you want to be notified when the campaign launches and receive a free metal active player marker, go to returntodarktower.com to sign up.